ALSO KNOWN AS: Psilotum nudum, skeleton fork fern

how to know

all branches

with three chamber sporangia

on trees or on the ground with no roots and no leaves at all

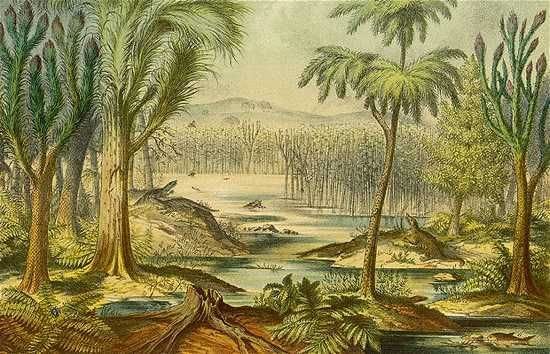

When all of land was tucked in the South Pole most of it was called Gondwana. All through the rest of the world colossal sea creatures made up the majority of life. This was the time known as the Devonian period around 400 million years ago, when spiral shells were formed, and sea creatures made up most of the living world. The world had a different chemistry back then. The ocean was slightly acidic, the poles were not glaciated in ice caps. It was warm. From this southernmost landmass strange and miraculous events took place at the water’s edge that would transform what was before merely scraps of rock and earth. Fish began to develop feet and rounded hip bones.

In the Time of Fishes

This was known as the age of the fishes, though the name does not suggest the fundamental change that was about to take place on the floating land that makes up our soil and earth. Mosses were beginning to harden their bases, and unfurl their leaves to take in more sun. Strange as they may look to us now in imagined illustrations from so very long ago, the plants worked together to become the place that our ancestors would call home. This became the place between the earth and sky, the canopies, the stained glass of leaves sheltering and weaving sunlight to make ecosystems of soil and water: they made forests.

If forests had not come the fishes may not have found the proper shade. Would the plants not have reached so high to the sun other plants and herbs would not have followed. If forests not come there would not have been such diversity of plant and animal life cultivated under their sheltering branches. Some plants climbed up the newly fashioned bark. One of those that left earth was a fern whose origin story is not entirely certain to this day. Though the plant continues to exist, after 400 million years, all over the tropical and subtropical regions of the globe.

Like a riddle, the whisk fern has no roots or leaves, flowers, or seeds. It doesn’t need anything but some sun, soil, and a bit of dripping rain to thrive.

The whisk fern is a vascular plant with stems delivering water and nutrients through the plant. This is pretty much all it has, though. This is the only vascular plant family that has no roots or leaves, but stands up tall. It doesn’t even look like a fern, much less any other kind of plant, except perhaps a seaweed. But, as with many plants, the secret is in the sex. The way plants reproduce tells you what family they are a part of. The pothos, for example, wasn’t classified in any particular family for many decades simple because it wasn’t seen in bloom. The roots of whisk fern look like the roots of mosses. They are called rhizoids. This is a root system that can suction to plants or rock surfaces. But it is found on the ground as well and can stand like a small clump of grasses almost in a forested area. Unlike grasses the whisk fern is made of separating stems known as dichotomous branching, meaning its stems split into Y formations in a labyrinth with many intersections. This is opposed to the lateral, or branched stems — like a coat stand.

The Latin name Psilotum nudum means ‘naked’. There were many bare stems back then. Plants didn’t have flowers, they didn’t open out their leaves like hands yet. To see the massive difference between those plants and these makes one wonder how plants will continue to adapt to the world around them in the millennia to come.

The whisk fern reproduces in a multistep process that matches the rest of fern plants. The whisk fern stands up straight if on the ground, but as a tree dwelling, or epiphytic plant, it hangs down like luscious green hair. Yellow lobes dot the stems, and which fill with spores. These lobes are called sporangia and they have three chambers that ripen until they pop, a release that sends the spores, as spare as dust, into the tides of wind that lead it far, sometimes hundreds of miles away. But usually in the canopy of trees the wind gets lost in the trees and settles. Once the spores find a home they submerge themselves into the soil or other nutrient rich surface, taking in the nutrients until they grow into a male or female gametophyte, which grows there, beneath the soil. One can live their whole life in a bracken forest and never see a gametophyte, yet they are innumerable barely below the surface of the soil. Once the gametophyte has reached maturity which can be around two weeks, the male will release sperm to be carried along the ground by rain or small streams to find a female. From there the asexual sporophyte - the one who carries the spores - is conceived and will grow once more in sparse stemmy formation. For the whisk fern, the female gametophyte lives in rhizoids of the sporophyte taking in nutrients like a little heart.

A Lost Twin

Plants have come in many shapes and forms. And the history of the whisk fern is debated. A mystery follows this particular fern because there is no fossil of this species. There is a species almost exactly like it, an extinct twin known as the Rhynia — which belongs to a different family of plant entirely.

And even though traces of the whisk fern have not been found it seems to mimic this long dead species.

In the ancient Devonian period many species looked like a bunch of sticks like the whisk fern. Yet those didn’t survive, which lends to the idea that the whisk fern might have transformed somewhere along the way, either to or from its current manifestation. Without leaves it gives its stems many jobs. The whisk fern is unique in that the stems have little white dots lining the body. These dots are the mouths of the plant, stomata, exchanging gases and photosynthesizing the sun. This lead to the belief that the plant could once have had leaves and adapted to not need them. Or indeed, the whisk fern could have had no leaves, developed them, and then adapted out of them again. Usually families of plants, like the Asteraceae can hold hundreds, or thousands of plants. But The only other plant in the Psilotacea family is the hanging fork fern, which hangs low in a pattern of leaflike stems.

Now the whisk fern has a complicated life. It lives in forests throughout the tropical and subtropical regions of the world. But it lives in greenhouses as weeds. It can grow quickly from gametophyte to sporophyte, bringing up thick vegetation if given the right, warm and moist conditions. Because of this it surreptitiously grows on plants in botanical gardens, though in the wild it is critically endangered. Its forested environments are being threatened.

Being so ancient the whisk fern has had a variety of uses. On the Indian subcontinent it is a stomach settler, easing nausea, working as an antibacterial in our bodies. Woven at its base, the whisk fern has been used to sweep and scrape away unwanted dust and debris, clearing space, making room. I like to think this fern has a secret it’s waiting to tell. The plant that formed when so much began, I like to think that after 400 million years it knows something about this great and ancient world and about what it means to transform in it, sweeping one identity away, and taking another, like that.

myth for whisk fern

music: Chopin Op. 22 sourced by https://www.classicals.de/chopin-collection

Not to be confused with pencil cactus, with tiny leaves and succulent stems.

Or rough horsetail. Horsetail grows by riverbanks and has deep brown ligaments. It usually is only one stalk sticking straight up.

Or coral - that’s an animal!!

Forager Friendly?

No - it’s critically threatened.

Sources

https://www.plantstogrow.com/P/4826/WhiskFernPsilotum

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hEuqrL_8bjw

https://www.britannica.com/science/Devonian-Period/Plants

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psilotum

https://plants.ces.ncsu.edu/plants/psilotum-nudum/

https://blogs.ifas.ufl.edu/seminoleco/2020/04/10/whisk-fern/

https://www.fnps.org/plant/psilotum-nudum

https://www.britannica.com/plant/whisk-fern

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psilotum_nudum

https://www.indefenseofplants.com/blog/2019/4/25/the-wacky-world-of-whisk-ferns

https://ucmp.berkeley.edu/plants/pterophyta/psilotales.html

https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=8PIMrKXZMNQ&t=0s

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YccfKkkBmrI

https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/AKVVN7RK4CNDCY8O

https://waynesword.net/PsilotumPC.htm