not the multi-pronged Big Bluestem

or the frothy seed-headed Junegrass

ALSO KNOWN AS: Pascopyrum smithii, red-joint wheatgrass, bluestem wheatgrass

How you know:

a striking bluish green

tight and rounded seed pods close to the seed head

1-3 feet tall, brushing our knees for miles and miles

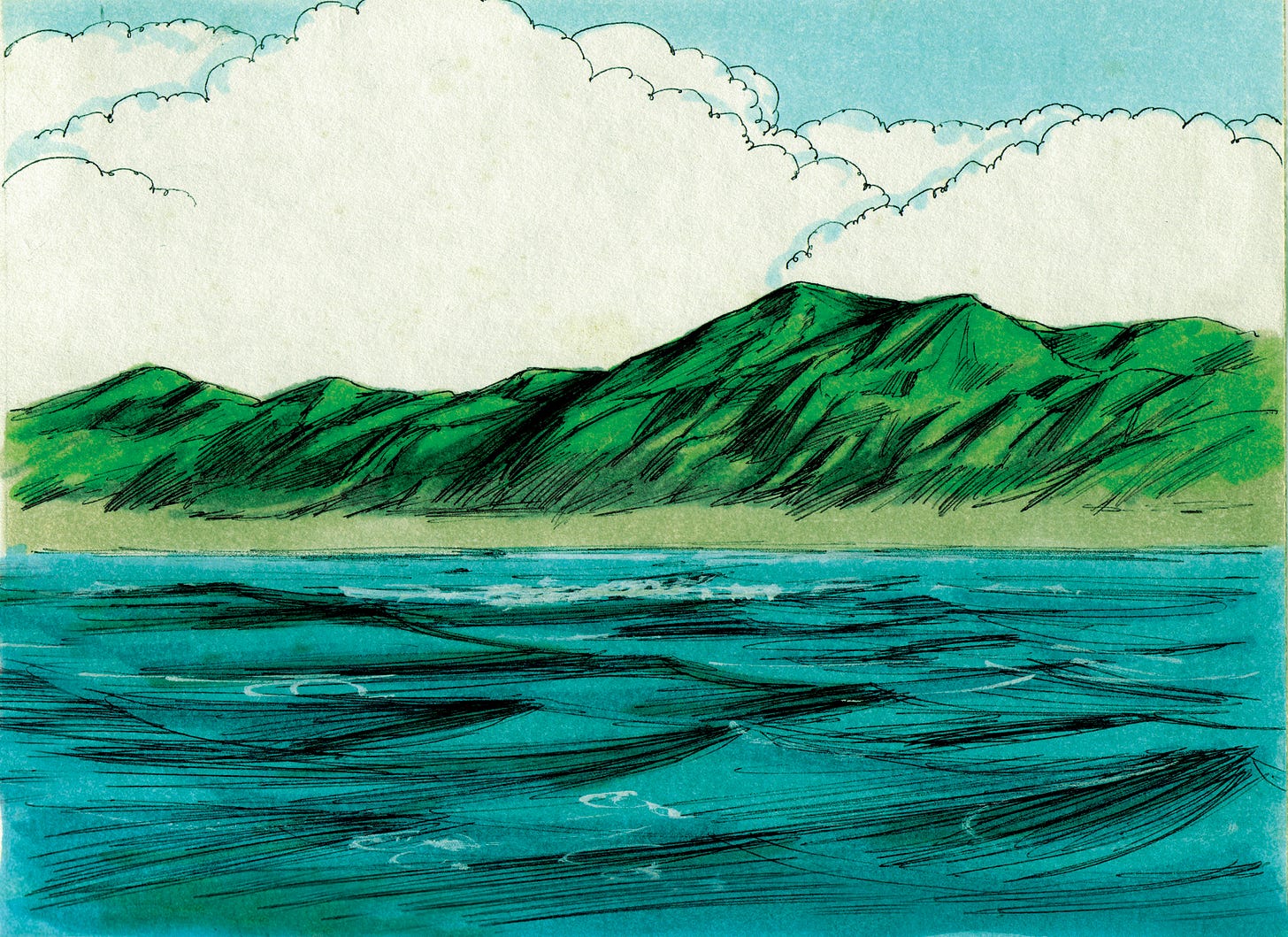

What is that small sea condensed into one blade, so blue, the color weaves into your eye from a great distance? Perhaps this chromatic effect is adaptive, because western wheatgrass does span a colossal landmass full of grazers. When I think of this grass I am reminded of the ancient Greek belief that Athena’s eye was the sun’s shimmer in the water. This dazzlement is one that has been cemented into the human psyche, as creatures who can never be too far from water. So when the sun shines generously on a body of water, something deep inside us calms: life is here. There are many things about the American West that lend to the idea of sea: the expanse of land and sky, the tall still mountains like frozen waves. Much of this place was, at one time in earth’s history, the bottom of the Western Interior Seaway.

But the plant that most resembles the Grecian concept of Athena’s eye is the western wheatgrass.

There are parts of the American West that don’t seem to end. Dwarfed by massive rolling hills, sometimes rocks take the shape of claw marks in the otherwise smooth inclines. Growing up in an area with mountains thick with deciduous forests, I experienced weather on the ground. Overhead a raincloud folded over the mountains or the sun shone down, but we didn’t see very far in the distance. There were simply too many trees. But weather is quite a different experience on the steppe, or the prairie. Weather is a moving thing, something which forms and rushes over the land with ferocity. Without many physical barriers, wind speeds up, creating tornadoes or lashing rain. So it’s no surprise that a common native plant to this region would be described as “aggressive” and “strong”. This wheatgrass is native to the prairie and steppe of western and northern US and Canada. It grows in tight bunches in lowland areas, knitting the soil together with its rhizomatic roots, keeping the land together while helping with drainage, soil health, and carbon storage, the plant is not really one to be fucked with.

Living up to its hearty reputation, western wheatgrass withstands flooding and a fair amount of drought, as well as the strain of continual grazing by elk, cattle, bison, antelope, and more.

What makes this plant aesthetically aquatic is the white coating along its sheath which gives that shimmer. With thick seed that grows tight to the seed head, western wheatgrass is buxom as grasses go. But the leaves are so ribbed they can feel like tiny knives when you run your finger along them. Western wheatgrass grows on hillsides; bottomlands; canyons; open woods; prairies; scrubland, and ditches with seasonal drainage. Not all of the grasses have seed pods because they grow right from that network of roots: new every year.

Western wheatgrass is prized by farmers aiming to be economical and sustainable because it can grow in a monoculture (though it is better to diversify the seed), it is perennial, and it’s very healthy for cattle.

Seed it in the early spring and it blooms in May and June. The earlier in the season the higher the protein content, which is good for grazers, small animals, bird. Pollinators congregate later in the summer.

a myth for western wheatgrass

Before this land was land, it was sea. But before the time of words and speech, the fickle ocean became tired of this place and slipped away, for better tides, leaving the land alone and in grief.

If you are looking, you will find traces of the ocean like this land is a giant basin of memory. The rocks remember the oceanic animals and plants. But those memories are merely written on the rocks’ shape and in the bones and veins that clung to them so long ago and buried over time. But the land loved being filled with water, so there are places where is opens up and embraces ancient shallow lakes, which remain as a small comfort.

And the land knew that water brought animals and plants, whom it loves, so it made the western wheatgrass a watery one, one that loves the rain and tolerates long periods of water and runoff. The land also made it good enough to eat, so the bison and elk and antelope could feast upon it. This grass now falls into the valleys, nooks, and crannies of the land, following every lower part of it as if filling it the way water would, glimmering in the sun and dancing in the wind currents, storing water in its seeds. And the land is happy again.

Forager Friendly!

If you’re feeding your sheep or cows, yes! They aren’t edible for humans, but farmers are working on making edible wheatlike grains.

Sources

https://www.wildflower.org/plants/result.php?id_plant=pasm

https://plants.usda.gov/DocumentLibrary/factsheet/pdf/fs_pasm.pdf

https://www.westernnativeseed.com/plant%20guides/passmipg.pdf

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=reUTQH4C-xQ

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/21/style/glitter-factory.html