ALSO KNOWN AS: Common reed, Danube grass, carrizo, Roseau cane, giant reed

How to know:

More than 15 feet tall by midsummer

Growing in colonies by the thousands generally, on sides of rivers and lakes

They grow alongside the skeletons of past year’s reeds

Puffs of inflorescence like dog tails flapping in the air

In bloom, the feathered seedheads range from mauve to a burnished gold

If there was a single plant that taught me about the deep complexity built into an ecosystem, it would be the reed, Phragmites australis. I learned this precisely because I saw the opposite of biodiversity in its crowded communities of clones. In fifth grade our teacher took us on a field trip to a swamp. I distinctly remember the autumn scent of decay. Or maybe it was spring: a transitional season marked by rain, and the soft heads of phragmites waved in the wind like specters from the water.

In the swamp I learned that plants can be aggressive to the point of self annihilation, creating an environment that would eventually implode upon its own weight. Lessons on the story of empire are written on the feathery and identical faces of the Phragmites australis.

It behaves so invasively in our environment of upstate New York that there is barely a body of water whose shores are not crowded by them. So once our teacher pointed it out, it covered my vision. An aggressive colonizing plant will not leave an inch of space. It rises even among the dead and dried growth from seasons before. For this reason alone it’s hard not to admire its tenacity, not so much for its aggressive growth patters, but in the undeniable strength of the fibers.

There are several varieties of phragmites that span the globe. But the most common is Phragmites australis. The Native American species of phragmites has less flowers, a purplish base, and does not stand as tall as the massive introduced species. The Phragmites australis has a rougher texture. As far as scientists have seen there is no hybridization between these plants.

Phragmites are a species from the grass, or Poaceae, family. While the name australis denotes an origin in Australia, there is evidence to suggest these plants are native to the Middle East, but some say they are native from the Shetland Islands down to Southern England. Though, I like to think they have adapted, primarily, to move, they are plants that follow us. Of all flowering plants, this one covers the largest geographical range in the world. They have learned to use humans to travel. Phragmites australis did not come to Turtle Island because people thought it was beautiful or useful. It came clinging to the ballasts of ships.

While it has not been admired for its beauty, they inspire a fearful respect. The phragmites australis are nothing if not striking. They can stand over 15 feet tall in legions of thousands. They are known as transition species, which play an important role between land and water and aren’t picky about the chemistry of their homes. They grow in brackish and freshwater, they can grow in the still water of ditches or along and meandering river. They grow in saltwater marshes. They grow wherever water and land meet.

Jointed culms - or stems - appear more like robots than the smooth cattail, or soft rushes. The reeds from the Eurasian continent are hollow in the center. Like all reeds, their culms also have lacunae, channels for oxygen to pass through the plants so as not to rot their formidable roots. The phragmites leaves are slightly serrated, almost sharp enough to cut skin. Lush featherlike seedheads nod in the breeze. Phragmites are pollinated by the wind. Their flowers are both male and female parts and spread their hundreds of seeds through wind or on water from August to September.

To help them fly, phragmites has given its seeds tiny wings of silvery hair.

But the seeds have relatively low viability rate. The phragmites spends its energy on its roots. The rhizomes are the main engine behind these massive thick monoculture communities. The main way they get around is grow clones from parts of the plant that are called stolons. These are above ground rhizomes that from which suckers, or plants will grow from. To the chagrin of shore protectors looking to uproot these plants to manage them, the stolons can reach 60 feet in length. While Phragmites taproots can grow ten feet below the muck in a single growing season. Plants have a beautiful relationship to their soils. Not only does the soil supply nutrition to them, but they act as divers, providing the soil with much needed oxygen that helps the process of decomposition take place.

Phragmites create monocultures that destroy wetland habitats. And yet, a contentious argument is simmering among scientists. Managed appropriately, Phragmites australis has its upsides. It manages water and keeping marshes at elevation while sea levels rise and, to maintain water chemistry, it partially desalinates brackish water. As phytoremediators, they take in heavy metals in the soil. Phragmites will literally transform water so that it is possible for wastewater, kitchen water, or otherwise toxic water to be redistributed back into the land. Phragmites sequesters water in floods and creates a network of rhizomes that promote soil stabilization. Because they fare so well in changing climates, phragmites could be a potential accomplice as we learn to work with what the land needs. But this is a contentious topic, because their existence means that other life in the ecosystem may not be possible. The plant doesn’t only choke out other plants, but its deep root system brings up carbon dioxide that is stored deep in the soil, undoing the native plants’ work in sequestering carbon from the atmosphere and releasing carbon dioxide into the air.

Management of phragmites has been best seen in controlled burns, but the specific or intentional care of Phragmites australis might make it an interesting plant to learn to live with and utilize.

Plants from the Poaceae family make up most of the world’s nutrition, from rice to bamboo, and these deeply common and far ranging reeds. The entire plant is edible, and depending on when it’s harvested, delicious and has been used as a sweetener in foods. Young shoots and roots contain up to 5% sugar. The rhizomes taste like the dull starch of potatoes. Medicinally they are diuretic, antipyretic (to reduce fever), and used to soothe the stomach.

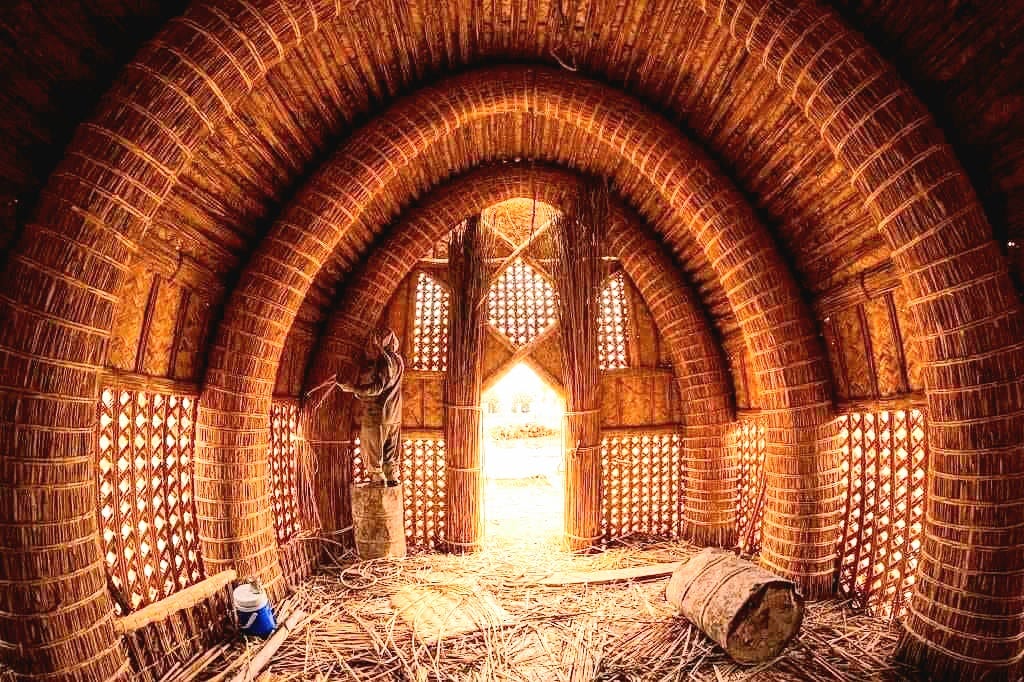

The ethnobotanical functions of phragmites are incredibly varied. Their simultaneous strength and flexibility allows for them to be used for thatching, basket, and paper making. They have also been fashioned into musical reed instruments or pipes for smoking. It has been used for wrapping the dead, in Turkey and the Middle East, and for making homes. It can be used as a great source of fuel for fires. Many myths allude to the inherent connection between storytelling and reeds -- for better or for worse. King Midas whispered to the reeds a truth about himself, that he had donkey ears and soon the word was out on account of the gossiping reeds. They sound a bit like they have ten thousand secrets we could know if only understood how to speak their language. Or maybe they are simply retelling the story of the folly of kings over and over again.

Myth for phragmites

Forager Friendly!

Yes, just please make sure not to redistribute more of the seeds. We don’t need more phragmites.

Not to be confused with cattail with its wax leaves and hot dog shaped catkin flower

Or the pampas plant, which has an even more lustrous flowerhead but is native to South America and can, indeed, grow further from the water - even on cliffs.

Sources:

https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/greatlakes/FactSheet.aspx?Species_ID=2937

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phragmites

https://hort.extension.wisc.edu/articles/invasive-phragmites/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DNGXs1Jgp24

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9d4j8wYUaQ4

https://www.britannica.com/plant/Poaceae/Distribution-and-abundance

https://sercblog.si.edu/jekyll-or-hyde-the-many-faces-of-phragmites/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3CKKYJtLM2Y

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5750922/

👍😊